Tunnel construction work is literally a backbreaking job. Especially when it comes to installing stress control elements (weighing 80 kilograms each) overhead. When Manuel Entfellner saw how the workers in the tunnel struggle with this, he decided to do something about it. We spoke with the Implenia site manager about his innovative stress control elements, the lack of error culture and what it takes to move tunnel construction into the 21st century.

*****

“I am in the tunnel every day whenever I am on a construction site and I’ve seen what a tough job it is for the employees. Installing compression elements overhead is hard work,” says Manuel Entfellner, who works as a site manager in tunnel construction. In the case of difficult geological and geotechnical conditions with a lot of mountain movement, stress control elements are used, which act like a buffer. They “absorb expansions from the rock so that the shotcrete does not crack.” A single element made of regular steel weighs around 80 kilograms. Sweat and back pain are inevitable, the risk of injury is high. Nevertheless, they are indispensable in difficult geological and geotechnical conditions.

Handy, lighter and more stable

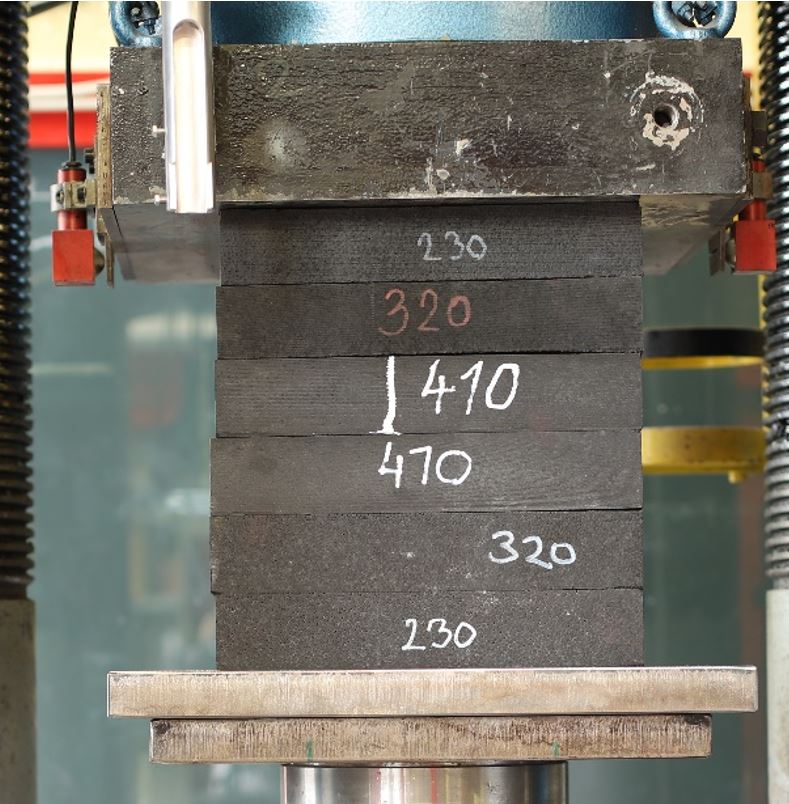

There had to be another way. “If I have to lift an element weighing 80 kilos every day, that’s not ergonomically advantageous.” The weight therefore had to be reduced. In a small on-site lab, he began exploring alternative materials and eventually developed block-shaped polystyrene elements to replace the steel behemoths that are common practice. Due to the combination of the new material and the simple shape, the elements are significantly more stable than before, and at only a quarter of the original weight.

Laboratory testing

Installation of the new stess control elements

“Why didn’t I think of that?”

Not everyone was convinced of the success of the project. “There were many critical voices, including within the company,” remembers Entfellner. “Nobody believed that such a light could withstand such heavy loads. An element has to carry 4,000 kilonewton (i.e. over 400 tons). It’s almost impossible to imagine. One thinks that concrete and steel can withstand it, but a ‘plastic’ element?”

At the construction services company Implenia, two people supported his research right from the start: Austria Managing Director Rudolf Knopf and Helmut Wannenmacher, Senior Engineer (and author of our blog post on “Artificial intelligence in tunnel engineering”).

The doubters have now become silent, because the product has proven itself and is already being used. “It makes work easier for the employees, it is a technical achievement and – what I particularly like – it is simply a very simple invention. Everyone grabs their heads and thinks, why didn’t I think of that?”

It is easily explained why no one has thought of this before: “Tunnel construction is a very conservative industry. People often view new ideas very critically. This is not comparable with injections or data management – tunnel construction has been at about the same level for the last thirty years. It may have improved in terms of machine technology, but little has happened in terms of support elements,” says Entfellner.

More openness

According to Entfellner, it takes mainly two things to take tunnel construction forward into the 21st century: new tender- and contract models and a culture in which failures are openly discussed.

“The tendering and contract model that we have in Austria makes it difficult to introduce innovations,” Entfellner wishes for more openness to new models. The problem: The phrasing of the tender for a planned construction is usually phrased extremely specifically. “Even if it might make technical sense, it is very difficult to agree on deviations from that contract. Executing construction companies should be involved as early as possible in order to be able to consider alternative proposals.”

No two tunnels and no two fault zones are exactly the same, and one-size-fits-all solutions are rarely effective. “Each tunnel is unique because the geological conditions are different. More openness is needed in the specialist committees. If you fail at any system – which often happens in tunnel construction in fault zones – then it is kept quiet and hardly ever published. Learning from mistakes doesn’t work that way, everyone starts over and repeats the same mistakes that have already been made on other construction sites or in other parts of the world.” Everyone likes to talk about success, Entfellner knows – but what we should talk about is failures.

*****

About Manuel Entfellner:

“Rock is my thing,” says Manuel Entfellner about himself. From an early age, the enthusiastic climber, mountaineer and amateur geologist knew that professionally, things would go in the direction of construction. After graduating from the HTL Bautechnik Salzburg, he initially did a bachelor’s degree in “civil engineering and industrial engineering” and then specialized in tunnel construction in the master’s degree.